Earlier in February adult education tutor Katja Robinson presented a lecture entitled Walter Crane and William De Morgan: Fairy Tales and Fantasy as part of a 5 week Arts & Crafts Adventures course for Edinburgh Council’s further learning programme.

The talk began with some mutual biography of these two key arts and crafts contemporaries, highlighting Crane and De Morgan’s connections with William Morris, who forms a backbone for the Adventures course per se. Crane shared Morris’s Socialist ideas which included providing illustrations for the Commonweal journal and designing the membership card for the Hammersmith branch of the Socialist League depicting a Morris-like smithy at the anvil forging new artefacts (as well as new ideas). De Morgan entered Morris’s circle in 1863 and became a friend, ally and colleague (although never a disciple) of Morris who exhibited, marketed and sold De Morgan’s work and incorporated it into decorative schemes.

One might argue that all three designers were concerned with creating beautiful things for the benefit of all attempting to dissolve the boundaries and traditional hierarchy between ‘high’ and ‘low’ art. Each craftsman in turn also displayed a highly idiosyncratic talent for capturing the rhythm of the natural world, its fauna and its flora, with a penchant for pattern to both soothe and stimulate the eye.

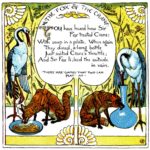

The lecture proceeded by laying special emphasis upon the highly imaginative, fantastical aspects of Crane and De Morgan’s oeuvres, as implied in the talk’s title. This is especially evident with regards a distinctive breviary of wondrous beasts, often sporting quirky, anthropomorphic tendencies, which feature in their designs. Intriguingly both men appear to have shared a particular affection for the avian; Crane used his long-legged namesake as part of his monogram especially for his ‘Toy Books’ and also featured this elegant bird in the memorable The Fox and the Crane illustration created for The Baby’s Own Aesop first published in the 1870s in which the protagonists attempt to outwit each other through their choice of crockery.

A similar curious combination can be found in De Morgan’s exquisite tile featuring a solemn, almost meditative, stork featured aside a chattering, grinning frog (c.1881) (private collection). Meanwhile a competitive playfulness is also found in the Eagle & Pike dish (1880-1897) (private collection) featuring the triumphant bird of prey, equipped with vicious talons and beady gaze, grasping the unfortunate, distraught fish whose torso disappears up into the upper left confines of the dish in a pulsating mix of wings and fins.

The Crane section of the lecture was divided into three sections: firstly his arts & crafts eclecticism and prolific career as an interior designer, secondly his influential achievements as one of the finest book illustrators of the Victorian period and finally his contribution to Symbolism, the latter proving relevant as not only is the enormous horizontal canvas entitled Neptune’s Horses (1893) arguably Crane’s most famous work but also because this is a highly fantastical image – a mesmerising, powerful brigade of horses rising and metamorphosing from the sea foam, galloping, crashing, splashing and thundering.

Meanwhile the hooves of Neptune’s equine team arguably have a distinctively webby appearance relating them to the mythical sea-horses, the hippocampi, a fine example of which one also finds featured on William de Morgan’s splendid Hippocampus dish (1882-1888) (private collection). The latter specimen is shown paddling about with great flourish in a swirling extravaganza of red and white denoting sea spray and waves equipped with glaring eye, bared teeth, pricked-up ears and streaming mane and becoming scaly half the way down its torso with a magnificent tail curling up and over to the right perimeter of the dish.

The lecture’s programme attempted to be as multi-media as its two arts and crafts protagonists and consequently short film clips were also featured. These included an excerpt from Disney’s Sleeping Beauty (1959) to complement Crane’s fascination with this particular fairy-tale as evident from designs for wallpaper, book illustration, masque/live performance (for the Art Worker’s Guild in 1899), political allegory for the Fabian Society journal and culminating in the enchanting triptych The Briar-Rose Cabinet (1905 Kelvingrove Art Gallery) and a screening of the 1999 ‘Surfer’ TV advertisement for Guinness directed by Jonathan Glazer which was surely inspired by Crane’s aforementioned painting of the tempestuous horses materialising out of the surf. Finally a clip from the Alice in Wonderland (1972 dir. William Sterling) complemented the De Morgan half of the session and drew the lecture to a close; De Morgan not only created the wonderful (albeit rather antagonistic) Eagle and Snark duo on his ceramics possibly harking (or should that be ‘snarking’?) to Carroll’s famous nonsensical poem of 1874 which the designer indeed possibly inspired but also provided Carroll with tiles for the fireplace of his living room at Christ Church in Oxford.

Carroll’s diary entry for March 4th 1887 documents his visit to de Morgan where he chose ‘a set of red tiles for the fire-place’ (unfortunately no longer in situ, apparently dismantled in the 1990s) known to have depicted a large sailing ship surrounded by a set of fantastic creatures including a dodo and a dragon. Carroll apparently used the tiles to illustrate his narration of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) for his visiting child friends. The film clip features the Dodo, Lory, Eaglet and Gryphon among others as well as a singing mouse (a diminutive creature also found on De Morgan’s tiles). One wonders whether de Morgan had been inspired by John Tenniel’s illustrations of the Alice books for his own designs and also whether it was the magic of mathematics which drew the author/Oxford logician and the designer into friendship and collaboration. The mathematical undercurrent of De Morgan’s ceramics designs has recently been explored in the superb Sublime Symmetry exhibition and accompanying catalogue.

Katja Robinson lectures at various sites in Edinburgh specialising in Victorian art history. She works in the art libraries of Edinburgh University and Edinburgh College of Art. She has been the Book Review Editor for The Pre-Raphaelite Society since 2014.