De Morgan volunteer, Vanessa Cumper, introduces you to Burne-Jones and shares some of her sketches of the man and his art in this week’s blog.

A man after my own heart Edward ‘Ned’ Burne-Jones took inspiration from the Ancient Myths, fables, stories, and poems, which I loved as a child, and still do. One of these stories was Sleeping beauty, which he depicted in his Legend of Briar Rose series (above), painted between 1886-90. His ‘Legend of Briar Rose’, inspired J. R. R. Tolkien (1892-1973) to write The Lord of the Rings. Burne-Jones’ influence transgressed from the canvas to the catwalk influencing fashion of the late 1800s, with the loose fitting Baroque-style heroines of his paintings. Morris & Co. sold his fabric designs so that women could recreate the look for themselves. More recently his influence has been felt on the catwalk. In 2013, designers, John Galliano, Rick Owens, Giles Deacon and Gareth Pugh amongst others revived the art of the Pre-Raphaelites. The runways saw sumptuous colours, romantically printed fabrics with the occasional nod to baroque styling, with a pre-Raphaelite sleeve here, a silhouette there.

A sketch of Burne-Jones by Vanessa Cumper

There was great significance with each of his first and middle names, he was christened Edward Coley Burne. Edward after his father, Coley was his mother’s maiden name, who sadly passed away a few days after his birth, and the second name ‘Burne’ was given after his aunt. It was not until the late 1870s that he hyphenated his middle and surname, so that he could be distinguished from the mass of Joneses. Edward Richard Jones, married Elizabeth ‘Betsy’ Coley in 1830, It was a condition of marriage by Betsy’s father that the family had a steady income, they had a little frame making shop at the front of their modest home in Birmingham.

At the age of 23 in 1856 Ned became engaged to Reverend George Browne Macdonald’s 15-year-old daughter Georgiana (1840-1920), they married in 1860. She was an artist in her own right, employed by Morris & Co. to paint tiles. Their surviving son Phillip became a portrait painter and their daughter Margaret married William Mackail, both of their children became authors. Ned and Georgiana’s grandchildren were not the only authors in the family one of Georgiana’s nephews was Rudyard Kipling, another famous nephew was the Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin. The couple had had another son, who’s birth was brought on prematurely when Georgiana contracted scarlet fever, sadly Christopher did not survive the disease, William De Morgan sat up with Ned offering companionship while his wife was delirious and the new-born had died. When I found this in amongst the research, I just fell in love with William De Morgan a little bit more, what an amazing man, what a good friend he was.

Edward Jones (as he was known at this time) travelled from his home in Birmingham to Oxford in 1852, to read Theology with the intention of entering the church (in 1881 he received an honorary degree). However, he became close friends with fellow student William Morris. They met Dante Gabrielle Rossetti (1822-1882) in 1855, by 1857 they all collaborated with Evelyn De Morgan’s uncle John Roddam Spencer Stanhope decorating the ceiling, walls, and windows of the Oxford Union’s library with murals (below). Encouraged by Rossetti, Morris and Burne-Jones travelled to Italy in 1859, inspiration struck the pair and on return Morris wanted to become an architect and Burne-Jones an artist. Burne-Jones’ biggest influences on this trip were Michelangelo, Andrea Mantegna, and Sandro Botticelli, suiting the romantic ideals of the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood.

Famous and respected during his own lifetime, he fell out of favour after his death, for about one hundred years. His work has enjoyed a revival, with his romantic watercolour Love Amongst the Ruins (below), based on the 1855 poem by Robert Browning of the same name, reaching a price tag of just under £14million in 2013, a group of three of his satirical sketches estimated at £2000. If we stay with Love Among the Ruins, the female model may have been either Antonia Caiva or the Greek model and artist Maria Zambaco, (1843-1914) with whom Burne-Jones had an affair. It is believed that the male model was Alessandro di Marco, who I featured in an earlier blog post https://www.demorgan.org.uk/alessandro-di-marco-evelyns-model-and-muse/. Although some claim that the male model was the harpist Gaetano Giuseppe Faostino Meo (1849-1925), who’s violinist daughter Elena had an affair (later marrying) with Edward Gordon Craig, the son of architect Edward Gordon and Ellen Terry. Their granddaughter Helen Craig is an artist and illustrator for the Angelina Ballerina book series.

Theatre was also an interest for Burne-Jones, designing the costume for Ellen Terry (1847-1928) when she played the role of Guinevere in the Lyceum’s King Arthur in 1895, a photograph of her wearing the costume can be viewed at the National Portrait Gallery. Burne-Jones preparatory sketch and watercolour are at the National Trust’s, Smallhythe Place. Ellen Terry was of course the first wife of George Fredric Watts (1874-1904). They were married between the years 1864 to 1877, although she had left him after just one year to return to the stage.

Burne-Jones was introduced to G. F. Watts at Little Holland House by Rossetti. A sensitive oil portrait of Burne-Jones was painted by Watts between 1869-70, exhibited at the sensational Grosvenor Gallery’s first exhibition. More than half of the painting taken up by Burne-Jones’ facial hair, which I found amusing, he had such a wonderful lustrous chin of hair, ZZ Top would have been envious.

William De Morgan met Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris in 1863, and he began working alongside the firm Morris and Co. (established 1862) soon after. He worked with Burne-Jones on stained glass, before being inspired to work on his famous ceramic lusterware. Georgiana talks fondly of William De Morgan’s “rare wit” and their long friendship, in her biography of her husband, Memorials of Edward Burne-Jones published in 1904, talking further about his many talents and how he visited them both at least once a week. G. F. Watts and his wife Mary were also great friends with William and Evelyn De Morgan, it is at Watts Gallery in Compton, that part of the De Morgan Collection is on display.

Like Watts, Burne-Jones was an influential artist during his lifetime, he became an elected member of the society of painters in Watercolour 1864. Unfortunately, the society disapproved of how he handled watercolour paint. In 1870 he caused a huge stir with his Phyllis and Demophoon (below).

Although at this time female nudes were commonplace, Burne-Jones’ Demophoon depicted as a full-frontal male nude was not acceptable, refusing to add drapery, he did not just leave the society, he withdrew from public life for seven years. These seven years were described by him as ‘blissful’ as he was at liberty to paint whatever he wanted to, without any deadlines, public scrutiny, or the angry criticism he endured his whole career.

Art dealer, critic and dramatist, Joseph William Comyns Carr (1849-1916) Burne-Jones’ patron, was the first director of the Grosvenor Gallery, making it the obvious choice for Burne-Jones when, he started exhibiting again in 1877. He exhibited three works, The Beguiling of Merlin (below), Days of Creation and Mirror of Venus on the east wall. Above these three paintings hung five allegorical studies of figures. Oscar Wilde wrote a rave review in the Dublin University Magazine, “Burne-Jones and Holman Hunt are the greatest masters of colour we have ever had……… Hunt, Burne-Jones and Watts are “the three golden keys to the gate of the house beautiful” It is in this article that he likens G. F. Watts to Michelangelo and discusses the “powerful portrait” of Burne-Jones by Watts.

The idea behind the Grosvenor Gallery was to create a platform for young unrepresented artists to display their work. Unfortunately, it closed in 1890, Comyns Carr had jumped ship a year earlier, founding the New Gallery with painter Charles Edward Hallé (1846-1914). Burne-Jones was at the height of his popularity and of course exhibited, as did Watts, Hunt and Leighton. The New Gallery, closed in 1910, briefly becoming a restaurant, then a cinema, which held the first UK showing of Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in 1938, it is now a retail store, but preserved as a Grade II listed building.

I mentioned earlier that Burne-Jones was very well known, he also had the good fortune to win many awards and accolades. 1891 he became an elected member of Art Workers Guild. He was made the Chevalier of the Legion of Honour, after exhibiting King Cophetua and the Beggar Maid (1884, shown below) at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1889, (p199 of the catalogue), the Eiffel tower was built for this exposition as it was one hundred years, since the French revolution. The Exposition attracted many well knowns including Buffalo Bill, Thomas Edison, Paul Gauguin, and Vincent van Gogh. G. F. Watts did not miss the opportunity either, he exhibited his world famous, even today, https://www.demorgan.org.uk/product/william-de-morgan-tiles-catalogue/ along with seven other works (p206 of the catalogue).

Burne-Jones became an elected member of the Royal Academy (RA) in 1885, but he resigned in 1893. Incidentally G. F. Watts was a member of the RA between 1867 to 1896. The RA hold a couple of his woodcuts that he submitted as illustrations to the magazine ‘The Good Word’. One of the woodcuts, The Summer Snow 1863 features a melancholy young woman leaning against a wall. The way that Burne-Jones drapes and folds the fabric of her dress reminds me of how Evelyn De Morgan also expertly tackles hers, which is not surprising when they were probably influenced by the same artists.

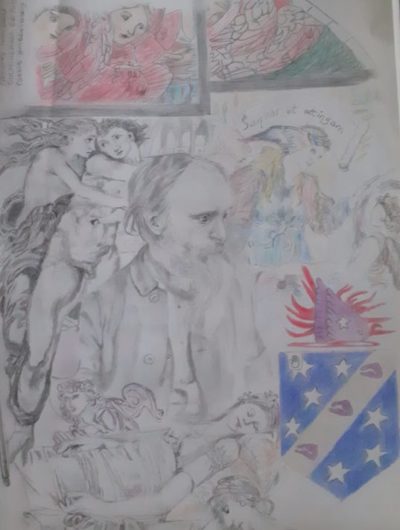

A year after Burne-Jones resigned from the RA he was offered the baronetcy of Rottingdean and the Grange in the parish of Fulham by Gladstone, for his work in the arts. Burne-Jones knew a lot about heraldry, using his knowledge in his cartoons and tapestry designs. It was at this point that he received Royal Licence to be called Burne-Jones, his full name thereafter was Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones. Some say he was uncomfortable accepting the Baronet, but as his son was keen to inherit, he accepted the honour. I wonder if that is why he chose the strip, along the middle of his Coat of Arms (below), to go from left to right, which is rarely used as it mean illegitimate. He also chose Wings and Stars, in heraldry stars symbolise honour, achievement and hope and wings are an emblem of protection. For the background to the stars he chose Azure, which signifies loyalty, chastity, truth, strength, and faith, while the wings are in purple which signifies temperance, regal, justice, royal majesty, and sovereignty. The wings are situated on the band which is coloured silver meaning truth, sincerity, peace, innocence, and purity. He even created a crest, which bore his purple wings in front of flames and his motto was ‘Sequar et attingam’, meaning ‘I will follow and attain’.

I really enjoyed all the twists and turns the research for this blog post took me on, creating so much to fit into my drawing. I was not sure that a simple portrait would show all the information I wanted to cram in. I decided to draw a sketch of his face emphasising the intensity in his eyes, because the Pre-Raphaelites saw him as an intense personality. I was intrigued by how his coat of arms and crest would look in full colour, feeling the only way to add this and all of the many facets of Burne-Jones would be in a collage. I was compelled to draw a collage inspired by the Dadaist movement, like them I do not feel anyone should be censored, as the watercolour society had tried to do to Burne-Jones.

References

Birmingham Cathedral Our Story, Windows. http://www.birminghamcathedral.com/windows/

Birmingham Museum. Portrait of Edward Burn-Jones by George Frederic Watts. https://www.birminghammuseums.org.uk/explore-art/items/1920P91/portrait-of-sir-edward-burne-jones-1833-1898

Burne-Jones. G. (1904) The Memorials of Edward Burne-Jones. The Macmillan Company. London. https://archive.org/details/memorialsedward01burngoog/mode/2up

Christies. (2019) ‘Beautiful Romantic Dreams’ – the art of Edward Burne-Jones.

https://www.christies.com/features/Guide-to-Edward-Burne-Jones-9460-1.aspx

Codell. J. (2014). “On the Grosvenor Gallery, 1877-90”. BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco, Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. https://www.branchcollective.org/?ps_articles=julie-codell-on-the-grosvener-gallery-1877

Cooper. J. (2018). Oscar Wilde in America. Oscar Wilde’s Cello Coat. https://oscarwildeinamerica.blog/2018/01/04/oscar-wildes-cello-coat/

Eiffel Tower. The Eiffel Tower during the 1889 Exposition Universelle https://www.toureiffel.paris/en/the-monument/universal-exhibition Catalogue from the exposition can be found here https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k9693253h/f229.image.texteImage

Fox-Davies. A. C. (2012) A Complete Guide to Heraldry. P240. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/41617/41617-h/41617-h.htm

Fury. A. (2013) Past Masters: Pre-Raphaelite Inspired Fashion. https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/fashion/features/past-masters-pre-raphaelite-insipired-fashion-8547487.html

National Portrait Gallery. Ellen Terry as Guinevere in King Arthur. https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw135922/Ellen-Terry-as-Guinevere-in-King-Arthur

Royal Academy. Edward Burne-Jones. https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/art-artists/name/edward-burne-jones

The Tate. (2018) The Seven Sides of Edward Burne-Jones. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/sir-edward-coley-burne-jones-bt-68/seven-sides-edward-burne-jones

UK Genealogy Archives. Burke’s Peerage, Baronetage, and Knightage 1899. Pp224. https://ukga.org/browse.php?action=ViewRec&DB=33&bookID=224&page=bp189900364

Wilde. O. (1877) The Grosvenor Gallery. Pp118-126 The Dublin University Magazine. Vol.90. (July-Dec. 1877). https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=njp.32101064302720&view=1up&seq=140