De Morgan Curator Sarah Hardy visits Evelyn De Morgan’s the Little Sea Maid in a new exhibition Ulysses in Forli, Italy.

In 1922 James Joyce published Ulysses, a novel probably more talked about than read. The title comes from the hero of Homer’s epic poem The Odyssey, in which Ulysses travels through real and imagined temporal spaces to ultimately confront, destroy and rebuild himself. Whilst Ulysses’s character develops over the world and a lifetime, Joyce’s protagonist – an Irish advertising salesman named Leopold Bloom – develops whilst trudging around Dublin in a single day.

The core narrative of developing human experience and self-referential contemplation exists in both. It is what keeps the classic text relevant and exciting today, as demonstrated in the popularity of Stanley Kubrick’s Space Odyssey. And it is perhaps for this reason that the Musei San Domenico in Forli, Italy, have named their exhibition after the man, not the original text.

After an epic journey of my own from London via Bologna, I arrived in Forli to install Evelyn De Morgan’s The Little Sea Maid into this exhibition.

The exhibition’s scope is incredibly ambitious, condensing the visual responses to Ulysses’s experiences by artists from antiquity to modernity, into one show. Over 50 sculptures and 150 paintings illustrate the epic poem, with a sharp focus on human experience and how that is depicted.

The exhibition opens with a stunning sculpture gallery of antique heads depicting Ulysses himself. Never poised or static, nor expressionless as marble figures often are, depictions of Ulysses are lifelike and dynamic, the inner workings of his conscious and unconscious mind carved into the stone and easily read, such as this classical response to Ulysses’s confrontation with Circe, who turns men into animals.

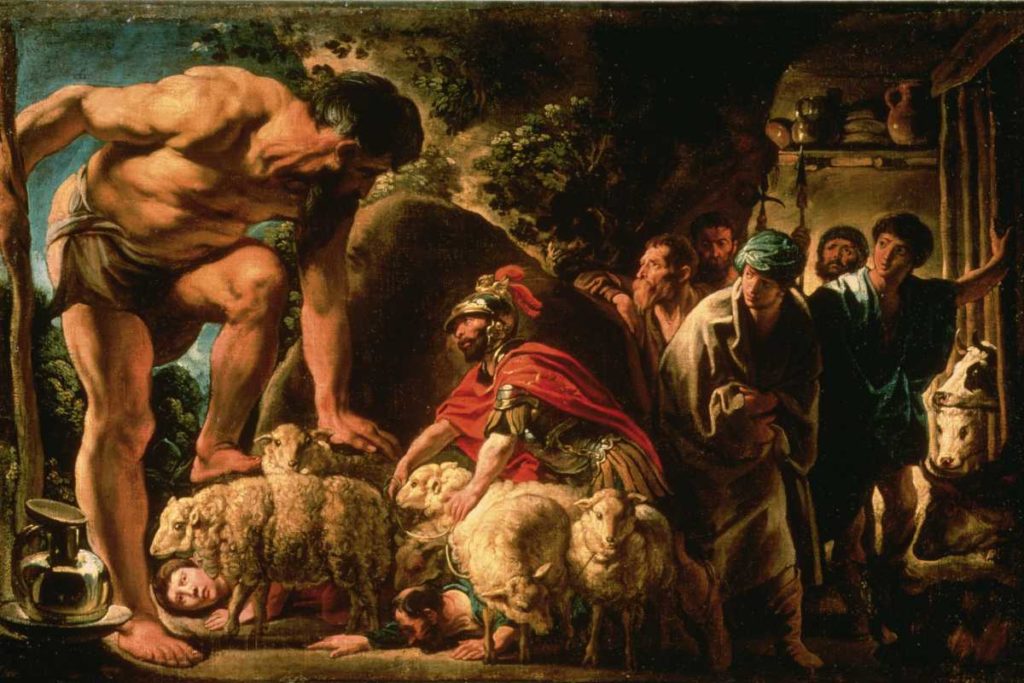

Transformation and transfiguration were perpetuated in Dante’s reworking of The Odyssey. He had not read Homer’s version and thus presents a darker, more visceral experience of Ulysses’s journey, where he is condemned, rather than evolving. This is depicted beautifully in Baroque paintings in the show with high drama and gory detail. Jordean’s depiction of Ulysses in the cave of Polyphemus, for example shows the man-eating cyclops giant Polyphemus and his terrified prey with dramatic colouring and scene setting, it almost looks like a painting of actors on the stage. The true Homeric notion that the outsider Polyphemus mirrors the lone Ulysses and hence the latter blinds the former so as not to have to see himself and be self-reflective, is lost in this purely narrative painting.

Odysseus in the Cave of Polyphemus by Jacob Jordaens (c.1635)

In the 19th century, the magic of mythology and human transformation was central to artist’s responses to the various literary sources then available of The Odyssey. The mermaid became a key figure for displaying the interplay with human conscious and subconscious and personal narratives of the self. The tradition is that the siren would lure sailors to wreck their ships on rocks, blamed for deaths at sea. In reality of course, they do not exist as more than a figment of the imagination, forcing fears of the sea, the journey, and becoming shipwrecked which live in one’s mind to be faced.

Little Sea Maid by Evelyn De Morgan

Evelyn De Morgan’s The Little Sea Maid is in good company with paintings by Waterhouse, Burne Jones and many others which personify Ulysses’s fears. The mermaid was never an actual anthropomorphic woman-fish hybrid, with an alluring, yet deadly voice, but a motif for the fear of the journey itself. Ulysses as a fearful lone wanderer also appealed to writers of the time, such as Nietze and Tennyson.

Set in the this context of this exhibition, De Morgan’s painting takes on a new meaning as a motif for unconscious fears. Perhaps not one she intended, but given her interest in literature and her Spiritualist leanings, one with which she could have sympathised.

The exhibition opens on Saturday 15th February and will be on show until 21st June.