In 1894, Evelyn De Morgan painted Flora a tribute to Florence, its Goddess, and the work of Sandro Botticelli (1444/5 – 1510). Flora’s elongated ‘contrapposto’ pose and tilted head can’t fail to recall the weightless, curvaceous form of Botticelli’s Venus, whilst the glorious blooms of spring in landscape and dress are clearly a direct reference to the Renaissance master’s Primavera.

Botticelli’s Primavera

Flora (1894) by Evelyn De Morgan

De Morgan visited Botticelli’s paintings on her many trips and extended stays in Florence, particularly after 1880 when her uncle, the painter John Roddam Spencer Stanhope, moved their permanently and provided her with a place to stay. She would visit Botticelli paintings and paint directly from them. Of course, her sketch after The Birth of Venus is well-known.

Evelyn De Morgan After Botticelli’s Birth of Venus

However, her sketch of‘ The Madonna of the Magnificat’ after Botticelli, detail: heads of two boys is less well known due to the rarity of her portraits with which to compare the sketch. But it is interesting to note that she isolated the two young boys from the tondo Madonna, rather than copying the entire image. Of course, this could be due to space restrictions in the gallery when trying to copy from the original, but perhaps the artist was also considering her own composition of a double portrait, which she would create of hr two young cousins in 1884.

‘The Madonna of the Magnificat’ after Botticelli, detail: heads of two boys

Double Portrait of Alice Mildred and Winifred Julia Spencer Stanhope (1884) by Evelyn De Morgan (C) Christie’s

Certainly, the high necklines with pin-tuck stitching detail which the girls wear in De Morgan’s arresting portrait recall the Renaissance dress of Botticelli’s boys. De Morgan also seems to have taken something from Botticelli’s approach to lighting the subjects from the front causing little shadow and giving the subjects full, rosebud lips.

The Botticelli portrait being auctioned today descended for generations in the Newborough family in northern Wales, where it hung in the family house, Glynllifon. It was kept in the private estate until the 1930s when it was sold, meaning that it was unknown to scholars and artists in the Victorian period. De Morgan would have been familiar with some of Botticelli’s other portrait, such as Portrait of a Lady known as Smeralda Brandini Woman at a Window which was owned by Pre-Raphaelite artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti and his patron Constance Iodines, who bequeathed it to the V&A.

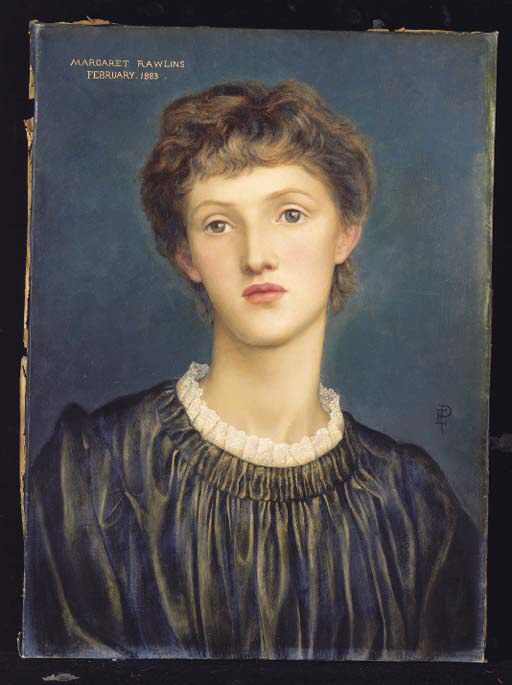

De Morgan’s Portrait of Margaret Rawlins shares certain characteristics with Botticelli’s portraits. The long neck, three-quarter length crop, piercing gaze, and blank backgrounds which intensify our engagement with the sitter. De Morgan’s handling of the pleats on Rawlin’s high-necked gown are clearly indebted to Botticelli’s exquisite capturing of the sheer fabric cascading over Brandini’s bust. The shared palette of Margaret Rawlins and Botticelli’s Boy with a Roundel are particularly notable – extraordinarily so when we consider she never saw the painting. De Morgan was a technically astute artist with an interest in experimentation with different colours and textures. It appears that she has used quite thick, dry oil for Margaret Rawlins which has enabled her to achieve the beautiful pastels of Botticelli’s tempera painting.

Margaret Rawlins by Evelyn De Morgan

Portrait of a Lady known as Smeralda Brandini

Woman at a Window

Portrait of a young man holding a roundel by Botticelli

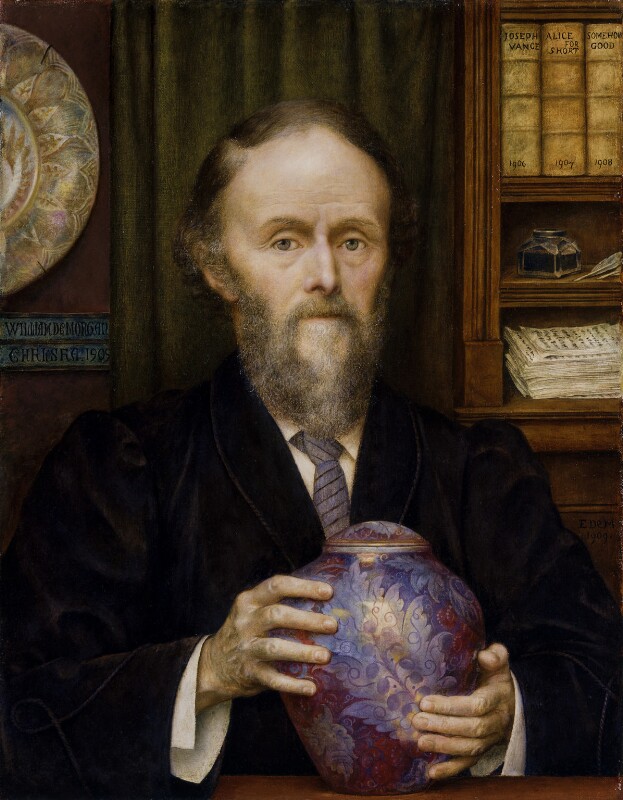

De Morgan’s most-loved portrait is of her husband William De Morgan. The artist was so intent on preserving her husband’s memory that she left this painting to the National Portrait Gallery in her will. In 1919 when she died however, the portrait gallery did not consider De Morgan reputable enough to acquire the painting and it stayed with the De Morgan family until the early 21st century when the bequest was finally made. This beautiful portrait also shares similarities with Botticelli pictures, particularly Portrait of a young man holding a roundel as both sitters clutch an object important to them. This feature isn’t unique in portraiture, but De Morgan clearly follows Botticelli in her approach to accurately capturing the anatomy of the hand, a difficult feature but which both capture with wondrous realism.

Portrait of William De Morgan by Evelyn De Morgan

Evelyn De Morgan’s work as a portrait painter is seldom recognised as she painted so few and those she did were of family members and close friends which have remained in private collections. Taking this opportunity to look at her portraits alongside those of Botticelli has revealed much about them, yet shows that there is still much to be understood about this element of the artist’s oeuvre.