Alexandra Earl, a Paintings Conservation student at The Courtauld Institute of Art, discusses how technical analysis has provided a valuable insight into Evelyn De Morgan’s materials and techniques employed in The Barred Gate (c.1914-19).

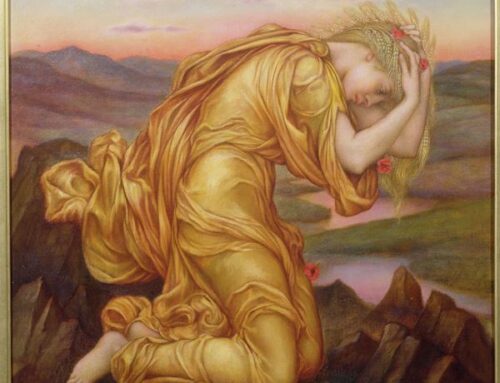

Normal light photograph, The Barred Gate, courtesy of the Department of Conservation, The Courtauld

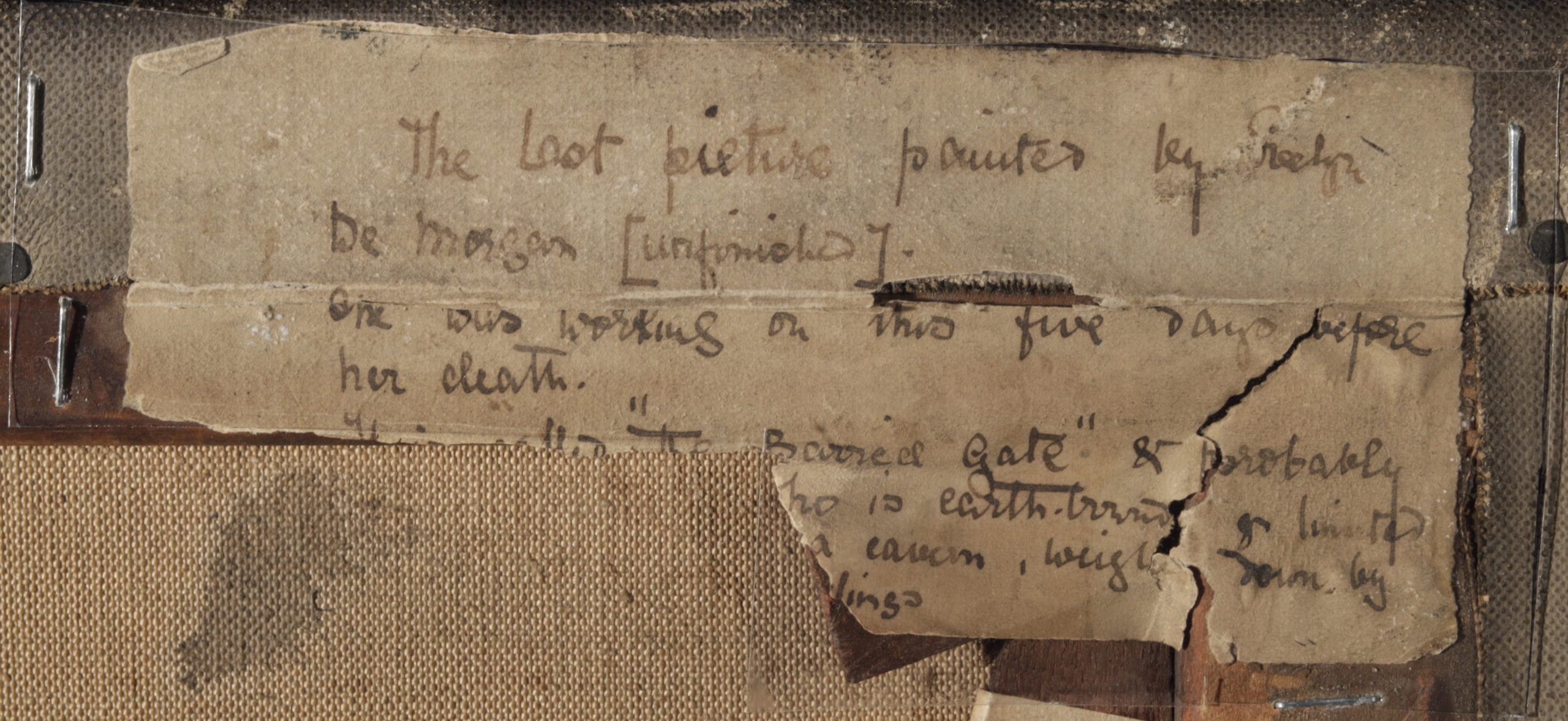

Photograph of the label on the reverse, courtesy of the Department of Conservation, The Courtauld

According to a label handwritten by the artist’s sister and founder of the De Morgan Collection, Wilhelmina Stirling, on the reverse of the picture, The Barred Gate is believed to be one of the last pictures that De Morgan painted and remains unfinished. The painting was possibly subjected to the effects of a fire in 1991 and it has never been displayed nor treated, until now.

Technical analysis conducted at The Courtauld Institute of Art, using methods such as infrared reflectography and X-radiography, has shed light on De Morgan’s enigmatic techniques and specific choice of materials.

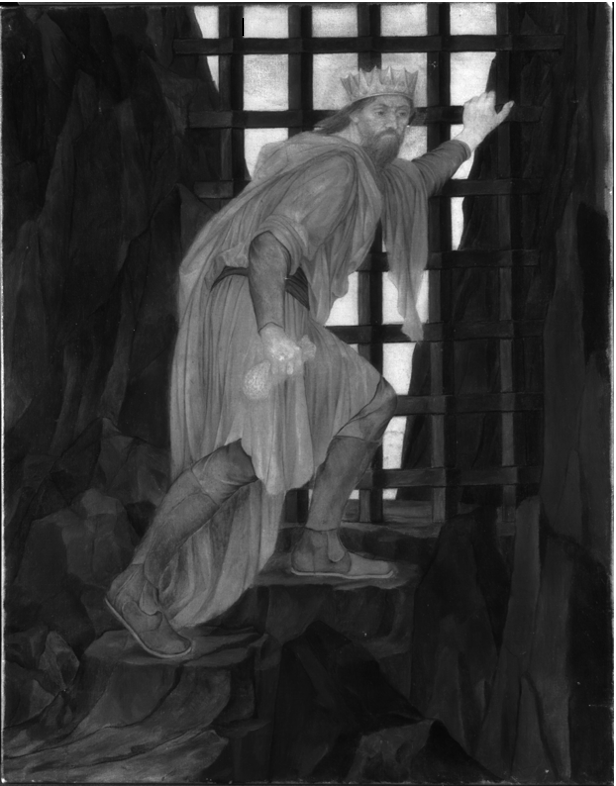

Infrared reflectograph, courtesy of the Department of Conservation, The Courtauld

Infrared reflectography involves the use of infrared radiation to penetrate below the paint surface to reveal underdrawing. Infrared wavelengths are preferentially absorbed by some painting materials which produce an image. Since carbon is highly absorbing, the technique can often be used to visualise carbon-based underdrawing in materials such as graphite or charcoal. Even though infrared reflectography did not appear to detect the presence of a carbon-based underdrawing in The Barred Gate, it is possible that De Morgan planned the composition in another medium transparent to infrared – such as red chalk. This coincides with the artist’s interest in Italian drawings and her own oil studies, in which she would often plan her compositions in red chalk prior to painting.

Ultraviolet light photograph detail, courtesy of the Department of Conservation, The Courtauld

Ultraviolet light photograph detail, courtesy of the Department of Conservation, The Courtauld

The exposure of paintings to ultraviolet light can help distinguish between varnish types, identify evidence of retouching and characterise certain lake pigments. In The Barred Gate, there is evidence of an uneven surface coating which fluoresces greenish-blue in ultraviolet light. This fluorescence, along with the glossy but discoloured appearance of the painting in normal light, suggests that it is a natural resin varnish. Upon closer inspection, it appears that this resinous media has been selectively brushed on sections of the gate, drapery and background – perhaps suggesting that a local use of varnish was part of Evelyn’s technique rather than the application of an overall varnish.

Also, Evelyn was not known to have typically varnished her works and this would be unusual considering the artwork is supposedly unfinished. The layering of varnish and oil paint was common in nineteenth-century practice, especially among The Pre-Raphaelites, as artists would often apply a varnish as an interlayer to saturate the colours. This research has informed the ongoing conservation treatment of the painting, which has involved the challenging removal of soot and dirt on the surface thus far.

X-radiograph, courtesy of the Department of Conservation, The Courtauld

X-radiography can produce extensive information about the construction of paintings and reveal later alterations that are no longer visible to the naked eye. An X-radiograph of The Barred Gate shows that the gate does not pass behind the figure, which may suggest that the figure was left as a reserve during the painting process. On the other hand, examination under microscopy suggests that the figure appears to have been painted first, with the surrounding rocks and gate having been meticulously applied afterwards. In particular, the X-radiograph emphasises the fine level of detail with which Evelyn renders the folds in the figure’s drapery and the distinct barred gate with precise and defined brushstrokes.

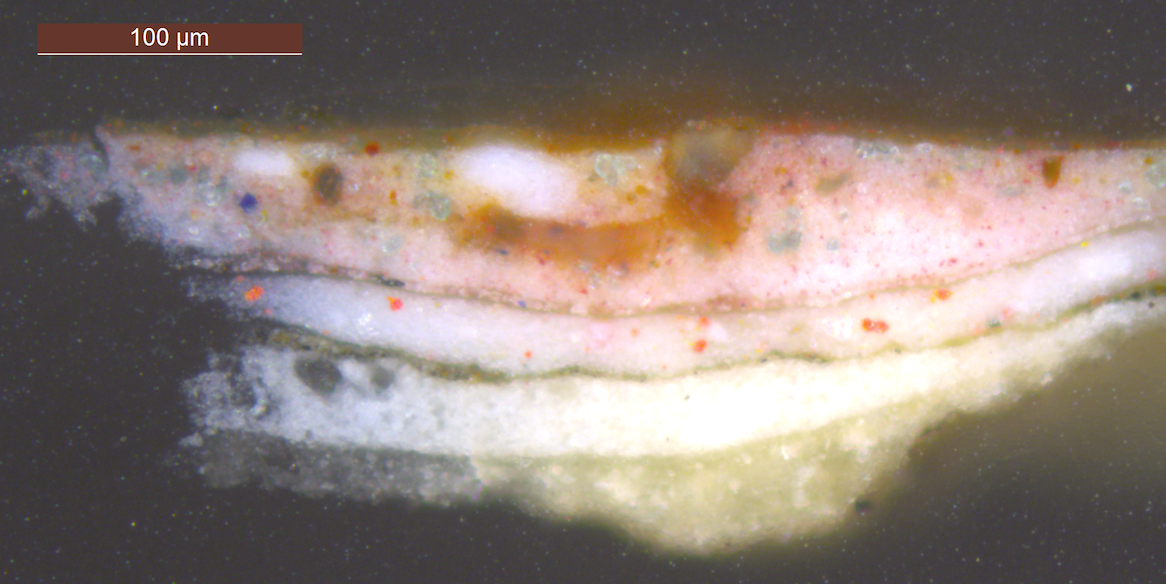

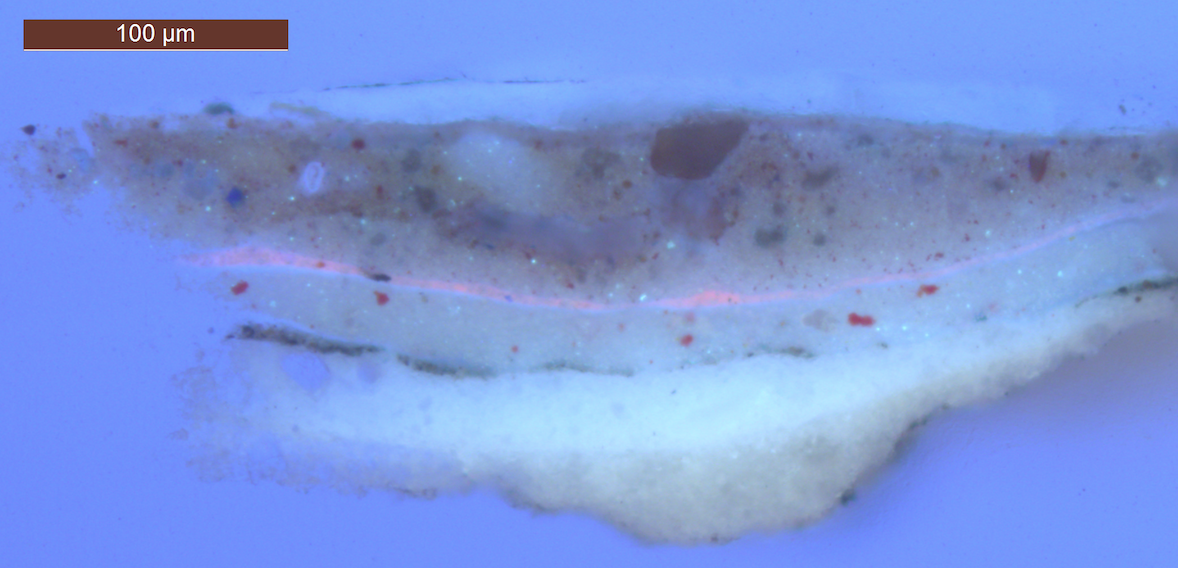

Paint cross-section in normal light, courtesy of the Department of Conservation, The Courtauld

Paint cross-section in ultraviolet light, courtesy of the Department of Conservation, The Courtauld

A paint cross-section is a minute sample, measuring less than 1mm in size, typically taken from the painting’s tacking margin or an area of damage. The sample is embedded in resin and then ground and polished. When it is illuminated under a microscope the layer structure and pigments present can be identified by their optical properties.

In a paint cross-section, taken from the pink sky, two beige ground layers are present. The lower layer appears to be primarily composed of chalk. Whereas, the upper ground is mainly composed of lead white. This is indicated by the presence of round opaque lead-containing aggregates, with sharply delineated edges that have a characteristic ring of fluorescence of the lead carboxylate (which forms when lead white is mixed with oil).

By the end of the nineteenth-century, colourmen (art suppliers) were known to occasionally apply two grounds: the first was often structural and comprised mainly of inexpensive chalk and the second was optical, with predominantly lead white for good hiding power. As both ground layers in The Barred Gate extend to the edges of the canvas, and the second is noticeably whiter and more opaque, it is likely both were commercially applied (perhaps by Winsor & Newton, as suggested by the colourman’s stamp on the back of the canvas).

Paint cross-section analysis also helped identify Evelyn’s use of pigments such as zinc white, vermillion and lake pigments. The paint cross-section shows a thin paint layer which fluoresces pink in ultraviolet light, suggesting the presence of a lake pigment. The paint layers also contain a mixture of earth pigments and vermillion. The latter of which can be identified due to its bright red and opaque appearance in microscopy. The inclusion of zinc white is also evidenced by its characteristic sparkle in ultraviolet light.

Surface cleaning The Barred Gate, courtesy of the Department of Conservation, The Courtauld

Technical examination has provided a unique opportunity to shed light on Evelyn’s artistic intentions, materials and techniques for The Barred Gate – all of which inform the ongoing treatment of this interesting painting. As analysis of The Barred Gate continues, and further research on De Morgan’s paintings is undertaken, it is anticipated that more tantalising information on the artist’s working practice will be uncovered.

(Endnote)

For further information, a technical and art historical study of The Barred Gate was recently completed as part of a collaborative research project called ‘Painting Pairs’ at The Courtauld. The presentations can be viewed on The Courtauld Research Forum YouTube channel and a report will be available later in June: