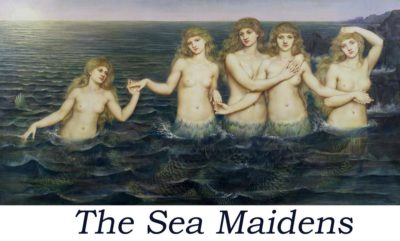

This post will not be a properly art-historical exploration of Evelyn De Morgan’s The Sea Maidens, but rather a reading of it today, an image with contemporary resonances and dynamics.

This painting, of five identical mermaids half-in and half-out of deep blue waters, may depict the sisters of Hans Christian Andersen’s Little Mermaid, who after their fifteenth birthdays were allowed to rise to the surface and observe the human world. Their flowing, voluminous blond hair and somnolent expressions suggests that this gathering of mermaids does depict the moment within Andersons’s story when, during the Prince’s marriage to the land-dwelling princess and not the Little Mermaid, the sisters surface with shorn locks to present their sibling with a knife to enable her return to the sea. In the fairy tale, the sisters have traded their precious hair to the sea-witch to gain a magical knife with which the Little Mermaid can kill the Prince and his bride to regain her tail; if she does not kill him, she will dissolve into sea foam.

What does this painting show, then, if we don’t know which episode within The Little Mermaid it depicts—if any? What are we to make of these mermaids today? Certainly as a starting point we must remember that these mermaids aren’t human, though they look humanoid from the waist up. What are they, if not human? There are several ways to think about this but I’m going to take us through the weirdest, most alien one, and one with contemporary relevance—that the mermaids, rather than being human, mammalian, or even fish, are a colony, like a coral, and are not distinct genetic individuals but budded clones of the same system. We’ll be back to that.

Oh yes.

But, Melissa, you say, they have bare breasts, and hair, and lovely big blue eyes and a really great lipstick colour, and other trappings of Western white human women!

To which I say, Yes! But we shall think a moment about the mermaid or siren before Hans Christian Andersen—that is, the dread creature whose beauty both physical and musical lured men to their deaths at sea, like the Sirens of William Etty’s monumental Ulysses and the Sirens (1837), Edward Poynter’s 1857 and Edward Armitage’s 1888 paintings, both called The Siren. By placing De Morgan’s erotically-intertwined sea maidens in context with their homicidal cousins, we can see that their ladylike loveliness and nubile nudity is not necessarily indicative of sexual reproductive capacity for the siren or the mermaid, but rather it is a lure—like a Page 3 angler fish, drawing hapless sailors in with the promise of breasts but offering only death.[1]

“The Angler (Lophius piscatorius),” Popular Science Monthly, vol. 16 (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:PSM_V16_D811_The_angler_fish.jpg)

So the mammalian appearance of their bodies may not be an indication of their place on the phylogenetic tree, but rather their hunting habits. Their tails, visible below the surface of the water, offer further evidence of their fishy nature rather than mammalian—scaled, iridescent, with sheer vertical tails rather than fleshy horizontal flukes, and diaphanous pelvic girdles. The appearance of warm pink flesh above water may reflect not the presence of warm blood but of chromatophores, colour changing cells like those in cephalopods—first described in English by Charles Darwin in 1860,[2] but even earlier by Aristotle.[3] The mermaids’ dainty limbs would not function well in the crushing depths if they were mammals; to survive the cold and the depths they would require much denser fat reserves and stronger muscles, and to be perhaps much larger—the size of whales, rather than teenage girls.

“Common Coral Building Zoophytes,” The Fifth Reader of the School and Family Series, Marcius Wilson, 1860 (https://archive.org/stream/firstfifthreader05will/firstfifthreader05will#page/371/mode/1up)

My original proposition was that these maidens were not individuals but a colony, budded daughter-cells of a coral system. This idea emerges from Daniel Mallory Ortberg’s “The Daughter Cells,”[4] a retelling of Andersen’s Little Mermaid. In Ortberg’s version, the mermaids (“you certainly wouldn’t think to call them girls, if you happened to see them”) are both individuals and part of a larger body politic, produced through budding or generated as colonies—not through paired sexual reproduction, or as the grandmother describes human mating, “they have to split off into two first and commit sexuality against one another.” In De Morgan’s painting, the intertwined limbs and tails of the sisters, as well as the clone-like similarity of their facial features (all based on a single model, Jane Hales) suggests that their relationship is not purely sibling, but closer. They are discrete physical instantiations of the same genetic body, where the absence of one of their members is made clear through the space between the leftmost figures.

Rather than reading the missing sixth figure as the Little Mermaid, gone to live on land, we might see it today as indicating the death of habitats through anthropogenic global climate change. Warming seas have caused coral bleaching events around the world, leading to the collapse of local ecosystems. Coral bleaching occurs when the symbiotic relationship between the coral polyps and zooxanthellae algae is stressed due to water temperature or pollution; the algae leave the coral tissue and reveals the white, vulnerable structure underneath.[5]

“Coral Bleaching,” National Oceanographic and Atmospheric

While coral can recover from this, it is dependent on the original health of the reef, the rapidity with which symbiosis and stasis are restored, and the avoidance of further bleaching events. To think about this in the context of De Morgan’s painting, we might see the Little Mermaid’s time out on land as her bleaching event, which only decisive action can reverse: the stronger colony bodies—the sister-cells—sacrifice some of themselves to bring their at-risk sibling the tool she needs to return to stasis in her proper environment.

While De Morgan’s paintings relating to the Little Mermaid cannot have been literally intended as commentaries on global warming, they are narratively nonspecific in their titles and compositions (The Little Sea Maid and The Daughters of Mist) as to allow for various reinterpretations and reframings of their subjects, interdisciplinary intellectual content, and contemporaneity. So it is possible, as Emma Merkling (PhD candidate, Courtauld Institute @emma_merkling) has done, to argue quite convincingly De Morgan’s paintings representing a directional, thermodynamic narrative of cosmic heat death, dissipating energy, and increasing chaos and entropy.[6] It is also quite possible to read these as somewhat syrupy, sweetly sentimental, somnolent story-telling pictures, illustrative and imbued necessarily with the narrative of Hans Christian Andersen’s tragic Little Mermaid. I think, however, that bringing works like these into contemporary discussions does not do the artists’ intentions a disservice but recognises that even highly aesthetic art-for-arts-sake paintings might have evolving meanings in culture. De Morgan was not a naïve sea-maiden, but an erudite, literary, and highly cultured artist working in a cultural milieu that is not totally dissimilar to contemporary academic-artistic circles, and it seems entirely reasonable to approach her work in with contemporary eyes.

[1] Fairchild, Herman L. “Curious Ways of Getting Food,” The Popular Science Monthly, April 1880, vol. 16, pp. 770-780.

[2]Darwin, Charles (1860). “Chapter 1. Habits of a Sea-slug and Cuttle-fish”. Journal Of Researches Into The Natural History And Geology Of The Countries Visited During The Voyage Round The World Of H.M.S. ‘Beagle’ Under The Command Of Captain Fitz Roy, R.N. John Murray, London. p. 7.

[3]Aristotle. Historia Animalium. IX, 622a: 2-10. About 400 BC. Cited in Luciana Borrelli, Francesca Gherardi, Graziano Fiorito. A catalogue of body patterning in Cephalopoda. Firenze University Press, 2006

[4]Ortberg, Daniel Mallory. “The Daughter Cells,” in The Merry Spinster, Kindle Edition.

[5]NOAA. “What is coral bleaching?” National Ocean Service website, https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/coral_bleach.html, accessed on 15/03/19.

[6]Merkling, Emma, “Entropy, Eternity, and the “Heat Death” of the Universe in Evelyn De Morgan’s Mermaid Paintings,” paper given at BAVS 2018: Victorian Patterns, University of Exeter, 29-31 August 2018.