Evelyn De Morgan passed away on 2 May 1919, leaving behind her a brilliant and beautiful collection of feminist, pacifist paintings and drawings which are today recognised as some of the most unique and magical of her time.

Just two years before her death, when her husband William had passed away, she had demonstrated her understanding of the importance and practical process of preserving an artists’ legacy through her generous gift of 1,200 drawings and a great number of ceramics by William De Morgan to the V&A. In addition, she asked artist and embroiderer May Morris to prepare an obituary for the Burlington Magazine, which was printed in two parts. As William had been much better known as an author at the time of his death, Evelyn’s actions were instrumental in ensuring his artistic memory.

It is strange then, that she didn’t take any such measures in ensuring her own material afterlife, leaving the dissemination of her estate to her brother, Spencer Pickering, and her husband William’s business partner, Halsey Ricardo. In her will, she explicitly states that all of the paintings in her studio should be sold in order to raise funds for the charity St Dunstan’s (now Blind Veterans UK), showing little regard for keeping the paintings together, or for their deeply personal messages. Instead, she saw them as financial assets which could benefit a charitable cause which she supported.

The Captives by Evelyn De Morgan, considered a ‘refuse’ picture by her brother and rescued for the De Morgan Collection by her sister, Wilhelmina

Wilhelmina Stirling’s note in the De Morgan Archive

Wilhelmina Stirling with her Collection

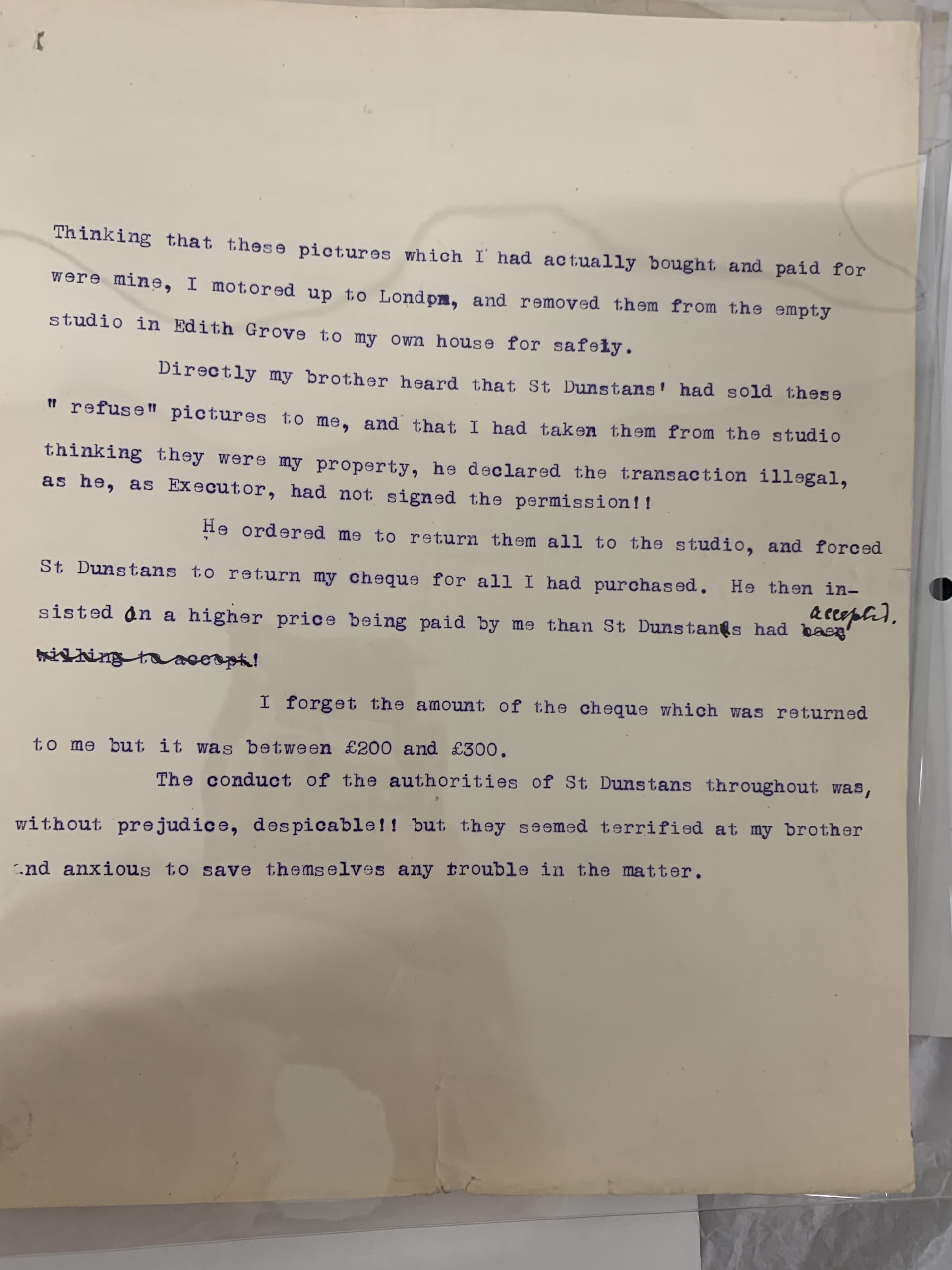

A particular line in Evelyn De Morgan’s will, referencing ‘refuse’ pictures which might not be good enough for sale, caused a family rift in the months following her death. Whilst Evelyn herself and her executors may not have seen the artistic value of her works and been keen to see them sold, Wilhelmina Stirling, her youngest sibling, did and went to great lengths to preserve these pictures and her sister’s memory.

A series of letters in the De Morgan archive reveal that a number of paintings in Evelyn’s Edith Grove studio at the time of her death were not deemed good enough to be sold. Wilhelmina, horrified, offered to buy them from St Dunstan’s directly, for the sum of £240. When her bother heard about this transaction, he forced St Dunstan’s to return Wilhelmina’s cheque and for her to return the pictures which she had already begun to conserve, since he, as executor, hadn’t signed a permission slip.

It seems that Spencer Pickering, after purchasing the better pictures for himself, was reluctant to let his sister have even those her didn’t wish to buy. His reasons for this are unknown, but a letter from Wilhelmina describes him as ‘neither mentally nor physically fit to be acting as an executor at such a time’.

St Christina giving her Father’s Jewels to the Poor, by Evelyn De Morgan

Eventually the situation was resolved and Wilhelmina Stirling’s wonderful collection of her sister’s paintings began.

Amongst the works she rescued were Evelyn De Morgan’s masterpiece St Christina giving her Father’s Jewels to the Poor (1904) and her beloved painting The Gilded Cage.

It is amazing to think these pictures were considered ‘refuse’ or substandard in some way, when they reveal so much of the artist’s world view. St Christina demonstrates her rejection of material wealth in favour of moral spiritualism, and Gilded Cage illustrates her feminist beliefs, as we see the young women trapped against her will in a marriage of convenience, not love, just like the canary in the gilded cage above her husband’s head.

Wilhelmina Stirling went on to eventually secure all of the paintings which her brother had purchased upon his death in 1922, and continued collecting De Morgan until her death. To ensure this collection was not broken up or undervalued again, she left it in trust for public enjoyment and education, work which the De Morgan Foundation continues to this day.