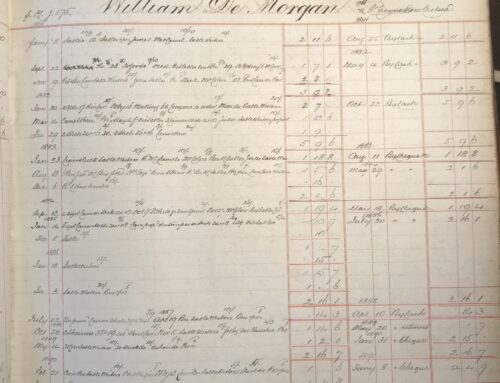

The Souls Prison house by Evelyn De Morgan

In 1904 Evelyn De Morgan’s younger sister Wilhelmina Pickering Stirling published her novel Toy Gods, a forceful portrayal of the falseness and hypocrisy of social contraints that were not simply imposed on women, but that women imposed upon themselves. But before looking at Stirling’s book it will be worth discussing some aspects of social constraints and how this was depicted by Wilhelmina’s sister, Evelyn De Morgan, as she too grappled with constraints placed on her by society and reconciled these with motifs of spiritual bondage in her paintings.

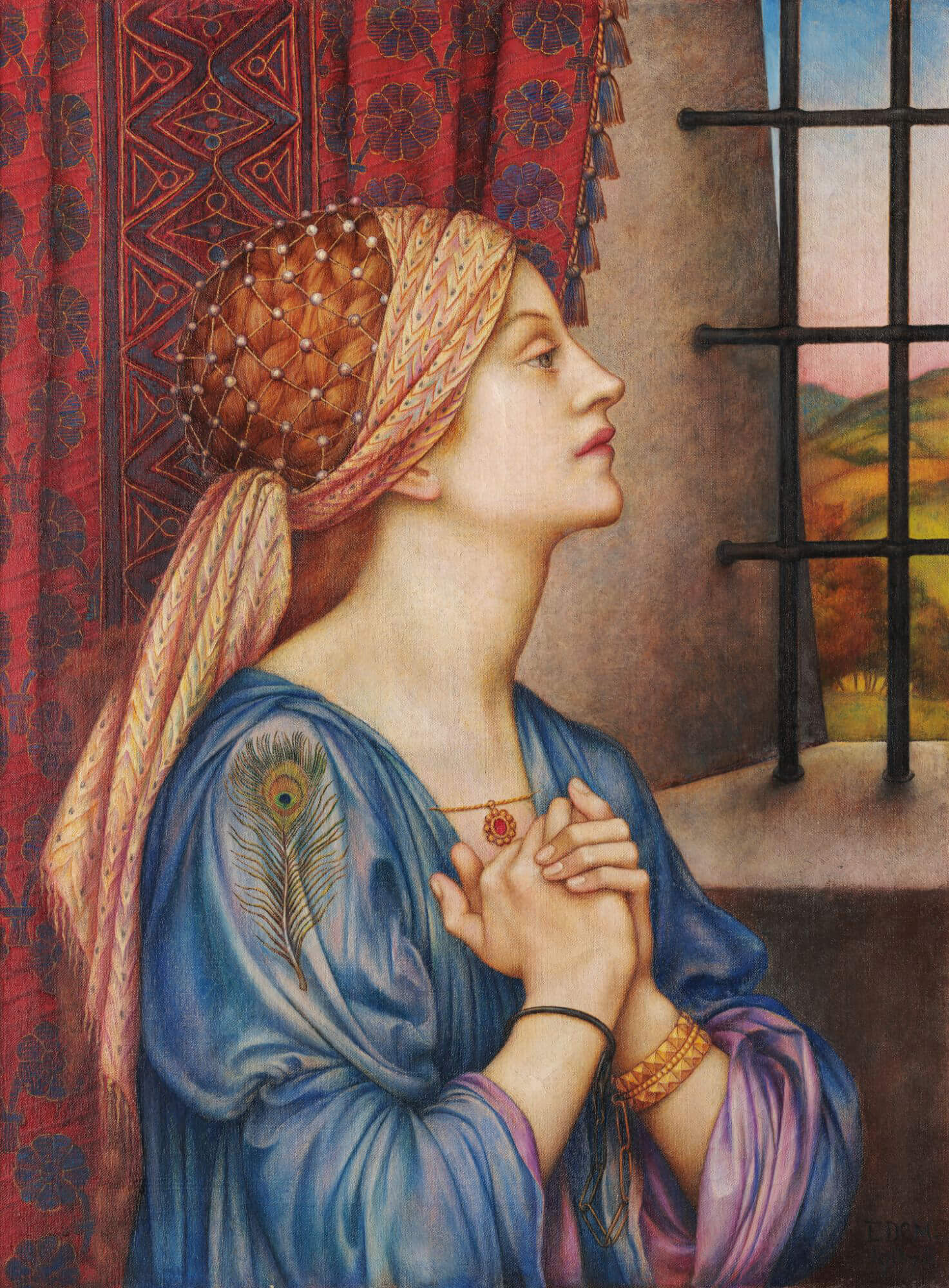

Bondage can take place, and be depicted, in many ways. Spiritual bondage has been more commonly expressed in literature – both poetry and prose – than it has in visual art. Evelyn De Morgan’s art is groundbreaking in that it depicted the emotional self-imprisonment of women. Sarah Hardy has stressed that she did this with so great a force that she was not truly a Pre-Raphaelite artist. And Lucy Ella Rose noted that “female captivity is a strikingly explicit, persistent and pervasive theme in [Evelyn De Morgan’s] work… Her plethora of paintings depicting the confinement of women…have been perceived as a series of spiritualist allegories of the ‘soul’s imprisonment’ or as the ‘bondage of the spirit’.”

Dr. Rose adds that while De Morgan’s paintings from 1887 to 1919 such as Hope in the Prison of Despair, THe Souls Prison House, The Prisoner, and The Gilded Cage “have been perceived as…allegories of the ‘soul’s imprisonment’ or as the ‘bondage of the spirit’, she consistently represents prisoners… in a feminist statement about the bondage of specifically female rather than ‘non-gendered’ beings.”

Hope in a Prison of Despair by Evelyn De Morgan

Among the twenty-three published books of the prolific Mrs. Stirling is Toy Gods, which was published using the pseudonym “Percival Pickering.” Percival was her father’s name; one might wonder what led the author of a strongly feminist novel to use a male identity. As Stirling had by 1903 published two novels (The Adventures of Prince Almero in 1890 and The Queen of the Goblins in 1892) under her own name, it is a mystery as to why she chose a pseudonym for this publication.

As copies are today quite scarce and it is not yet available digitally, a simplified synopsis follows: Toy Gods tells of seventeen-year-old Amelia, the second daughter of the wealthy Admiral Bradshaw. After his wife’s death and “in his dotage” the admiral married his cook but had neglected to change his will, so that after both their deaths their daughter Amelia had nothing. She has to live with her maternal aunt, Mrs. Burgess, a charwoman. Hearing that her much-older half-sister Muriel lives luxuriously on Park Lane, she determines to meet her. Uninvited, she goes to meet her at a ball. Amelia goes dressed as a moth, showing her liveliness, and her legs! She is both open and kind: returning home late that night Amelia encounters a shivering beggar-woman, for whom she takes off and gives her own shawl.

The Prisoner by Evelyn De Morgan

The Gilded Cage by Evelyn De Morgan

Muriel is quite affected by their encounter. Wishing to help her sister, Muriel sends her to school, gives her lessons, finally presenting her to Society at a ball. But Society proves itself a false god: in learning to be a “lady” Amelia has lost her ability to be natural, to be herself. She finds herself terribly constrained and emotionally miserable. Muriel too is constrained: her husband is an invalid completely confined to bed; her friendship of Sir Geoffry offers some relief.

Amelia falls in love with Sir Geoffry, who perhaps predictably shows himself a true cad: he proposes marriage to the young girl (and the chapter ends with them kissing passionately) but the next day he rescinds his promise, acting as though nothing had happened. Amelia furiously confronts him. “I’ve that much of the ‘lady’ in me,” she says to her sister, “I don’t want him back.” Not knowing the match is off, Mrs. Burgess tells her niece, “You’ve gorn up in the world and left us all behind.” Amelia answers: “I’ll tell you what a ‘lady’ is: it’s talking correct grammar… never looking as if you were enjoying yourself, walking well, talking well, fooling well.” But Amelia’s anger has helped her recapture her sense of being natural. She is now free.

One major difficulty I found with Toy Gods is that Muriel and Sir Geoffry engage in long philosophical discussions, ones that that (for me) detracted from Amelia’s story. But the story has power, and I find it unforgettable.

Wilhelmina Pickering Stirling’s family itself embodied both the privileges of Society and a strong tradition of independent questioning. Society had stipulations for men as well as for women: while one brother, Spencer, became a chemist who discovered what is known today as Pickering stabilization, in Life’s Little Day Wilhelmina writes that her brother Rowland “determined to enter the medical profession, in spite of strong opposition, for those were days when to be a professional slayer of a visible enemy was an honorable calling, but to be a professional combattant…of germs and microbes…was not the occupation of a gentleman…” How ironic to read in these Covid-19 times!

In those years, too, writing novels was not the occupation of a “lady.” We are fortunate that today the De Morgan Foundation continues to fulfill Wilhelmina Stirling’s vision in so many ways.