Emma Merkling writes about an exciting new archival find at National Trust’s Wightwick Manor: a list of book titles in a sketchbook from ca. 1877, the first primary evidence of Evelyn De Morgan’s potential intellectual resources.

De Morgan scholarship has long suffered from gaps in the archive. Evelyn De Morgan (1855–1919) left us with no adult diaries or notebooks, nor any other first-hand written record of her life or artistic practice. Only a few of her letters have been recovered, and these reveal little about the formidable mind behind them.[1] The absence of important primary material in De Morgan’s own hand has presented a particular issue for scholars writing about her life and work, making it difficult for us to understand much about her resources, influences, and interests as an artist, and forcing us to rely heavily on secondary sources in our analysis of her art.

It is for these reasons that I am particularly excited to share my recent discovery of a list of book titles written by De Morgan in the back of a small sketchbook around 1877. The list is the first direct, primary evidence – in De Morgan’s own hand – ofher adult interests and potential intellectual resources, and paints a picture of a bright, curious, and ambitious artist with an unusually broad range of interests.

Fig. 1: the first two pages of the list of titles. Note that the second page includes an excerpt from John Keats’s epic poem Hyperion (1820, Book 1).

The sketchbook (NT 1288042) is housed in the archives of Wightwick Manor, Wolverhampton.[2] It is small, only 10 cmhigh and 15.5 cm wide, and consists of about 40 leaves, almost all of which are covered with sketches and notes. There is much direct evidence linking the sketchbook to De Morgan. Notes in her handwriting appear throughout, alongside preliminary sketches for her paintings Cadmus and Harmonia (1877), Ariadne in Naxos (1877), Venus and Cupid (1878), and The Grey Sisters (1880–81). These designs also suggest a date of no later than 1877 for the sketchbook. The list of book titles – also in De Morgan’s handwriting – appears on the last four pages of the sketchbook, and consists mostly of texts published in the 1860s and ‘70s.

Fig. 2: the final two pages of the list of titles.

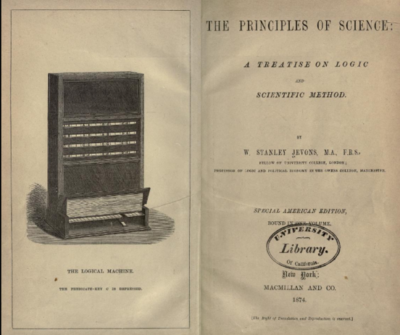

Some of the titles confirm what we already know or believe to be true about De Morgan’s influences, based on her paintings and preparatory studies, while others offer tantalising glimpses into unusual interests that could provideexciting new avenues for research. In the former camp are texts like John Addington Symonds’s The Renaissance: An Essay (1863), a cultural history of a period whose influence on De Morgan is clearly visible in her art.[3] In the latter, there are scientific texts like William Stanley Jevons’s The Principles of Science: A Treatise on Logic and Scientific Method (1874), and George Henry Lewes’s Problems of Life and Mind (1874). The list also includes cultural criticismand socio-political commentary like John Ruskin’s The Crown of Wild Olive: Three Lectures on Work, Traffic, and War (1866) and William Rathbone Greg’s Rocks Ahead, Or the Warnings of Cassandra (1874), closer examination of which could further enrich our understanding of De Morgan’s socio-political interests and the manifestation of these in her art.

Fig. 3: frontispiece of William Stanley Jevons’s The Principles of Science: A Treatise on Logic and Scientific Method (1874)

Since my own research interests lie primarily in the intersections between De Morgan’s art and her scientific context, I am particularly intrigued by the references to a range of scientific texts. These references, which suggest that De Morgan was indeed interested in topics like mathematical logic, the scientific method, and psychophysiology, open a new window onto her intellectual and artistic processes and reorient how we think about her work. They also enrich our understanding of the intersections between science and the arts in Victorian Britain more broadly. This discovery has already impacted my research significantly, and my dissertation will be the first to address De Morgan’s reading list directly and consider these sources in depth alongside her work.

In an area of study which has been marked by an absence of concrete insights into De Morgan’s resources, I trust that this discovery will furnish De Morgan scholarship with primary source material that has been lacking, both supporting existing arguments and paving the way for new ones.

Emma Merkling

The Courtauld Institute of Art

May, 2019

For questions about this research or to get in touch with information about De Morgan and her resources, please contact me at emma.merkling@courtauld.ac.uk. You can also find me on Twitter at @EmmaMerkling. I am grateful for the guidance of De Morgan Foundation curator Sarah Hardy, who alerted me to the existence of the De Morgan sketchbooks at Wightwick Manor, and would also like to thank the Wightwick staff for helping me locate and photograph the sketchbooks.

[1]Beyond the letters, the only resources in De Morgan’s own hand are the juvenilia owned by the De Morgan Foundation: some childhood notebooks and a teenage diary. The De Morgan Foundation also owns a small sketchbook full of interesting notes and marginalia whose authorship is contested, but which the Foundation believes to be by De Morgan or her uncle, John Roddam Spencer Stanhope. I believe it is more likely the latter than the former: the handwriting and drawing style are significantly different from De Morgan’s, and none of the sketches in the book correspond with artworks she made. As for De Morgan’s adult writing: according to her sister (Wilhelmina Stirling), Evelyn and her husband William also authored a book of spirit writings, The Result of an Experiment (1909), but as this was published anonymously and no primary records of their authorship have yet been found, this attribution cannot be considered concrete evidence. Evelyn’s completion of two of her husband William’s novels (The Old Madhouse, 1919, and The Old Man’s Youth, 1921)after his death and shortly before her own also deserves mention in discussions of her writing; however, these are arguably of lesser interest in terms of understanding her artistic practice.

[2]The sketchbook is also identified in the Wightwick Manor archives as WIG/D/176.

[3]This reference might alternatively refer to Symonds’s seven-volume Renaissance in Italy (1875–1886), the first three volumes of which would have been published by the end of 1877. These titles include vol. 1, The Age of the Despots (1875); vol. 2, The Revival of Learning (1877); and vol. 3, The Fine Arts (1877).