Probably produced by William De Morgan around the time he was an art student in the late 1850s and early 1860s, these sketches reveal much of his art before ceramics. Originally in a sketchbook, they were cut out by an art dealer in the 1970s and framed to be sold individually which they were in 1975 by Christie’s. These two drawings recently resurfaced on the open market and the De Morgan Foundation were able to acquire them with the generous assistance of a Patron. Adding them to the De Morgan display Look beneath the Lustre in the Gallery at Wightwick Manor allows a deeper understanding of De Morgan’s broad achievements in art and design. Being works on paper that demonstrate the artist’s working process, these drawings are a good fit for this particular display. Not only do they reflect the collecting interests of the Mander family who built Wightwick and left it to the National Trust they also invite us to ‘look beneath the lustre’, or encourage us to consider how artworks are made. It is the first time these small-scale sketches have ever been on public display.

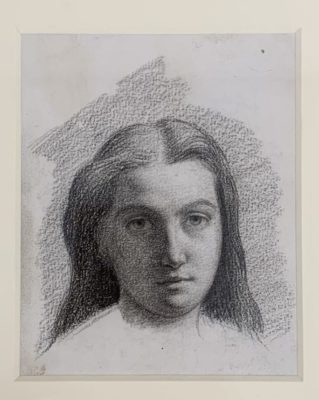

Pencil Sketch of a Girl (unknown)

c.1860

By William De Morgan

Portraits usually serve to tell us about the subject. But since we do now know who the sitter is in this beautiful drawing it is more valuable for our understanding of the artist’s technique than as biographical material.

De Morgan has used a high-level light to cast a strong shadow over the face to give interest to the composition. Using a soft pencil, he built up layers to create the darker areas and left the textured paper white for the highlights. What he achieves is a dramatically lit rendering of the girl’s captivating gaze.

We rarely think of William De Morgan as an artist, his ceramics are better known. But when he was 20 years old he decided he would train as a painter and set his sights on the prestigious Royal Academy Schools. Such was the Academy’s reputation, he had to pass an entrance examination to join. Only through rigorous training at Cary’s Bloomsbury Academy, where Millais had also trained, did De Morgan master the art of studying from antique sculpture and pass to the schools.

The small-scale of this portrait shows that it was probably made quickly as a sketch and something De Morgan made alongside his formal artistic training in a sketchbook for private practice. Living at home with De Morgan when this sketch was made were three of his younger sisters, Anne, Helena and Mary, and so it is likely that he coerced one of them to pose for him.

Design for Stained Glass depicting the story of the Good Samaritan

c.1860

By William De Morgan

Training at the Royal Academy Schools was tedious work. Students were required to spend years perfecting their drawing before they could begin to learn to paint. It would appear that this disillusioned William and so when he met the inspirational William Morris in 1863 he was encouraged to abandon his painting and focus on becoming a designer. By the 1860s many churches were being built or redeveloped in the Arts and Crafts style and Morris & Co. had a monopoly on providing bespoke designs, providing artist friends of Morris the opportunity to work in glass. Like Burne-Jones, Ford Madox Brown, Simeon Solomon and many other Victorian artists, De Morgan began designing stained glass for Morris.

During the decade that De Morgan made stained glass, he would create religious scenes in watercolour and gouache for exhibition and to develop his ideas. Wightwick is exceptional as the only public collection to have a William De Morgan religious watercolour in its collection. You can See ‘The Finding of Moses’ on display in the Billiard Room.

We believe that this tiny blue silhouette is a quick sketch by De Morgan to capture figures in a pose. One robed figure bends over another who is sat with his legs out on the floor. Even though the small sketch has been quickly executed, De Morgan clearly conveys the interaction between the figures as one stooping to help the other. It is therefore probably a sketch for the Good Samaritan, a Biblical parable which encourages us to help our neighbours.

If you look closely, you can see that De Morgan has highlighted the robes and figures in white, perhaps experimenting with how the design would look with light pouring through once it had become a stained-glass window.

Being an inventor by nature, De Morgan became more interested in the process of making stained glass, than the designs for it. He noticed that if fired in a kiln starved of oxygen, glass painted with silver nitrate in order to stain it yellow would mis-fire leaving the silver metallic particles deposited on the glass’s surface. This reminded De Morgan of lustreware ceramics and he moved away from working on stained glass redeveloping lustre and making his own plates and tiles from 1872.